The article is divided into three parts. The first section discusses academic style in the context of appropriateness, then focuses on noun phrases. I will then examine the use of shell noun structures to improve the cohesion of a text, as this shows the reader how the ideas and concepts presented in the text are connected. The second section broadens out to discuss the writing process from reading strategies for source texts, how synthesis grids can be used to develop critical reading strategies. I then discuss paraphrasing, synthesising sources and the use of reporting verbs and nouns and in-text citations to develop the authorial voice of the writer. The last section is broader again and discusses the use of corpus, the impact of the knowledge building of different academic disciplines on the genres and lexical and grammatical structures that writers for a particular discipline require, and then discusses what impact this and the advent of LLMs may have on assessment of academic writing.

Academic style

The French sociologist of education, Pierre Bourdieu (et al. 1994), once wrote that “Academic language is no one’s mother tongue” and students often arrive at university with little real understanding of how they are expected to write academic texts. This lack of awareness is often exacerbated by the effects of students being remorselessly drilled for international preparatory exams, leaving them blinkered to

the range and variety of texts they are expected to produce.

To counter these issues, the first thing to do is to introduce the concept of academic style, and the best way to illustrate good style, is

to compare it with examples of less appropriate styles. As space is limited, the following examples, generated by an LLM and then modified, are short but hopefully illuminating. Of course, a longer text will provide multiple examples of the target academic style appropriate to the academic discipline of the students.

Text 1: The full utilization of advanced communication technologies fosters enhanced collaboration and knowledge exchange. These technologies propel productivity and innovation across diverse industries and academic disciplines.

Text 2: When you use fancy tech stuff to communicate, it makes it easier for everyone to work together and share ideas. That way, you can get more stuff done and come up with cool new things in different fields.

The students are asked in which context each text is appropriate, and then identify the language features that led them to their answer. Moving away from the binary correct/incorrect to that of appropriateness for a specific context is important. Firstly, it focuses students’ minds on the purpose of writing a particular text. For example, it is possible students may be required to write for a general audience. Also, style varies across disciplines with ‘I’ more commonly used in Philosophy than in Medical research. Finally, while a single word verb often has a more specific meaning than a related phrasal verb, and it is therefore more appropriate in an academic text, the issuing of too prescriptive lists of dos and don’ts is unadvisable.

With these caveats taken on board, we can now focus on the language structures that make Text 1 ‘more academic’ i.e., the use of a long noun phrase, this/these + dummy noun, and that makes Text 2 ‘less academic’ i.e., you, conversational language, and phrasal verbs and generally verb heavier. I will discuss noun phrases and academic cohesive devices in more detail later, but here I want to discuss the teaching of tenses. Research has discovered that just three tenses, past simple, present simple and present perfect account for a whopping 98% of the verbs used in academic writing (Biber et al. 1999). This should not surprise us,

as academic writing concerns theory and concepts and the data that supports or challenges the postulates of a researcher. In contrast, spoken General English which focuses on what people did, are doing, will do etc is verb heavy.

Other activities to illustrate appropriacy for academic style could be to compare a more academic text with an IELTS essay, or by asking students to rewrite spoken English sentences, so that they are more academic, or vis versa. Here, the most important thing is noticing the structures. This can be challenging for the less proficient students, who do not have the linguistic dexterity and range, but it can also be an issue for more proficient students, who understand the text and so do not feel they have to analyse it.

Noun phrases

A noun phrase can be comprised of a single noun, but noun phrases are frequently found with pre and post moderating phrases. These moderators can include other nouns, and it is important that we identify the head noun to correctly understand its meaning (see Figure 1).

Noun phrases are an essential element of academic writing, as they allow writers to give very precise descriptions in a concise way. As their high lexical density can be challenging for students, I suggest that there are a few steps that we must take to teach them how to unpack their meaning. Firstly, they need to identify the components of a noun phrase i.e., circle the head noun and label the word classes – articles, adjectives (premodifier) prepositions, relative pronouns (postmodifiers). Students can then explore writing long noun phrases by starting with basic non-discipline specific examples i.e., cat – the cat – the black and white cat that lives …. and so on. They can practice rewriting pre modifiers as post modifiers. This also can be used as a diagnostic tool to assess the groups’ grammatical awareness, and once determined, I would suggest a little and often approach is better than a solid turgid block. Finally, discipline specific examples can be identified in textbooks and then recycled into short texts written by the students in class.

Cohesive structures beyond conjunctives

Research has shown that L2 students overuse conjunctives in their writing (Sing 2013). This may be the result of inadvertent feedforward from international language examinations. In this section, I suggest that the use of this/these + noun i.e., this process or such + noun i.e., such ongoing trends, can be used as an anaphoric device (i.e., refer to something mentioned earlier in the text) or as a cataphoric device (i.e., refer to something mentioned later in the text) to improve the cohesion of a text. In the literature, these nouns are referred to as dummy or shell nouns, as they only have meaning in relation to what they are referring to in a text. Again, students can be encouraged to read extracts from texts from their reading list to notice which dummy nouns are used most frequently in their discipline. Students can write short texts to practice this feature.

Once students have been introduced to academic style, nouns phrases and shell nouns, with their concomitant grammatical structures, it is time to move from short exemplar texts employed for noticing and recycling to engaging with longer texts.

Reading into writing

In this section, I will seek to demonstrate that reading is an essential element of the academic writing process, as only through reading multiple texts can a student develop sufficient understanding of an issue to write an assignment. To successfully accomplish this there are three interconnected components: developing reading skills, purposeful note taking (the synthesis grid) and writing the first draft (see the section below on paraphrasing, synthesizing and voice).

Academic texts can be defined as factual texts, whose evidence is derived from multiple sources. Thus, a writer of an academic text, be it an esteemed professor or a humble undergraduate, must be able to read, understand, and collate the opinions and data from many texts. Teaching the students to read for a purpose, to skim and scan a text for information, to identify the macro structures of a text i.e., problem-solution, cause-effect etc., have all been proven to develop the reading skills of L2 learners. One way to teach these skills is the following task. Select a text that is about four pages long. First, strip out the subheadings and figures and then give them to the students as a handout. Give them a few minutes to read and make predictions about the text. Then give the students the text and have them do a skimming task, then a scanning task. Finally have the students identify specific sections/sentences in the text that can be used to address the assignment. Later, the text can be cannibalized for useful language/ grammar structure noticing activities. This task can also be repeated as an assessment task, or as a perennial homework assignment, where the students independently identify a text and then go through the stages listed above.

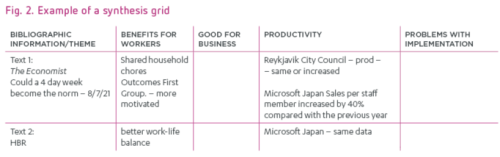

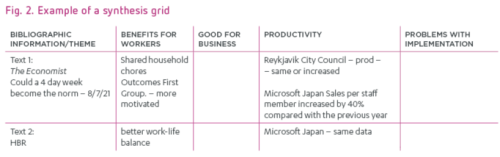

Students often read a text without contrasting it to other texts they may read on the same subject. One way to encourage students to see the interconnections between texts is to use a synthesis grid (see Figure 2). The student reads the first text and identifies the main themes of the text in relation to writing the assignment, these are written at the top of the synthesis grid. Then the student adds notes in the relevant box in the grid. The student then reads the next text and identifies overlapping or new themes, and then again adds more notes and themes to the grid. As this is an exploratory process, and themes may be amended or divided and notes need to be moved, it is advisable to use a Word doc rather than pen and paper. The intersections between the text: where they agree, and where they disagree, should be readily apparent. A theme can be the source of information for one of the paragraphs of the assignment, and by providing an overview of the arguments and data across several texts, it can develop criticality. If used properly, a synthesis grid can be a timesaving stage between the source texts and the first draft of the assignment. A synthesis grid is particularly useful for writing different genres of essays and the literature reviews of longer assignments.

Paraphrasing, synthesising, and authorial voice

Once students have completed the synthesis grid they should have a clear idea of both how they will address the assignment and the content they will include. At this point the student can use their notes to decide which parts of the source texts they will spend time on paraphrasing, and how they might combine these together in a synthesis. Before I go onto discussing how choices concerning in-text citations and reporting verbs and nouns can be used to present the authorial voice of the writer, I will examine paraphrasing and synthesizing information in more detail.

The best way to start teaching paraphrasing is to show a range of attempts at paraphrasing a short text. The students decide which is the best attempt and why it is successful. By examining this version, the tutor can reveal the key elements of paraphrasing: the meaning is the same, information order is changed, use of synonyms, changes in word class, active/passive and which key terms should be kept the same. The tutor can then suggest a methodology for paraphrasing:

- underline the key terms you are not changing.

- underline what you are planning to change – maybe use a dictionary to check for synonyms or the word family.

- put the original text away and write your paraphrase.

- finally compare your version with the original – is the meaning the same?

- add the appropriate in-text citation.

Good paraphrasing takes practice and time, and it can be a struggle for students, as it challenges their linguistic dexterity. Yet the payoffs for this effort are also significant and should be emphasized by the tutor. However, as LLMs are very adept at paraphrasing, I suggest that some practice should be done in semi-exam conditions i.e., no devices rule.

Synthesising texts simply means you are combining two or more texts together to show contrast i.e., While Smith (2010) argues ….. , Jones (2021) believes that, or to show agreement i.e., Both Smith (2010) and Jones (2021) agree that …… . It can be employed to demonstrate a wider and deeper understanding of the literature and the use of multiple sources can strengthen the position being forwarded in an assignment. To practice this skill, give the students two or three short texts that either agree or disagree with each other and have the student write a synthesis of the texts. LLMs are a good source for these type of texts, the website www.procon.org is also useful.

Once students have got the idea you can go on to look at situations where the positions of two sources are not polar opposites, and there may be an overlap in their opinions. Or they may well agree, but they have chosen to emphasize different aspects of an issue. Again, the above synthesising techniques can be used to show a more nuanced understanding of the source texts.

Finally, whenever a student takes an idea or data from a source text, they must include an in-text citation. This is both to avoid being accused of plagiarism, and to show that they have engaged with the discipline’s literature. There are two types of in-text citation: author led, and information led. Author led in-text citations start the sentence, and as the name suggests they are employed when who said this opinion is considered important by the writer of the text i.e., Smith (2000) states that….. . Information led in-text citations on the other hand are placed at the end of the sentence, and they are used when the information is considered more important i.e., 99% of cats prefer it (Smith 2000). The choice of which one is used in any given instance depends on what the writer is trying to achieve and is therefore part of the wider paradigmatic shift to writing source-based texts. Student’s struggles with the mechanics of in-text citations can be emblematic of them grappling with the underlying concept that their writing needs to be source-based and how they develop their authorial voice. Repeated practice and patience seem to be the only solution to this problem.

The constant companion of the in-text citation is that of the reference. Never wait until the end to do this! Every university has a how to guide for this. Make the students write some references from a range of sources that you have provided them. After repeatedly saying – alphabetical order, and why are you adding bullet points – the students will hopefully have produced a suitable reference list.

While the choice of the content of an assignment can demonstrate the authorial voice of the writer, it can sometimes resemble a list of other ideas and data. To show their voice more a student can choose from an extensive range of reporting verbs or nouns to accompany an author led in-text citation, as the author of the text can show to what extent they agree with the source they are citing. There are many good online materials available. I suggest this one: Verbs for Reporting (adelaide.edu.au). In addition to reporting verb and nouns, students can add adverbs i.e., Smith (2000) convincingly argues that … . Tangentially, when choosing an online source always look for the Top-Level Domain of ac for UK university websites or edu for US or Australian universities, as these are far more likely to be reliable, and they will not try to sell you anything!

In the final section, I raise the broader issues of how a corpus can be used in academic writing, the impact of an academic discipline’s knowledge building on its writing requirements, and discuss the implications of what I have outlined for assessment regimes.

Corpus

A corpus is simply a collection of texts i.e., the British Academic Written English Corpus (BAWE) British Academic Written English Corpus (BAWE) | Coventry University. It can be used to give us real world examples of the collocations, lexical features and grammatical structures that are most used in a particular academic discipline i.e., Chemical Engineering. There are various tools we can use to search these linguistic features or indeed create our own corpus i.e., Sketch Engine Create and search a text corpus | Sketch Engine.

Knowledge building and genre

Martin (2011) suggests a typography for different academic disciplines on the basis for how they create new knowledge. Put simply, the Science disciplines are described as having hierarchical knowledge structures with new knowledge being built by how a data set is interpreted or how a new theory or technique supersedes a previous one. In contrast, knowledge building in the Humanities is characterized as being horizontal knowledge structures where competing theories interpret the world i.e., a Marxist historian provides evidence that social class is linked to health inequalities, while a neo-liberal focuses their research on the tax burdens faced by entrepreneurs. This idea is further developed by Nesi and Gardner (2012), whose book Genres Across the Disciplines – student writing in higher education, demonstrates the clear connections between an academic discipline, the writing genres associated with it, and the resultant lexical and grammatical structures that writers for a particular discipline require. This has clear implications for those who teach academic writing to students studying a particular academic discipline, for the more we know about what our students write, the more we can tailor our courses to best meet their needs. While the sometimes-opaque nature of assessment regimes at universities, and the limited status that language teachers often have within a faculty are very real barriers to accessing the required information, this should not stop us from trying. To this end, Martin’s article and Nesi and Gardner’s book provide us with a solid theoretical basis to achieve our objectives.

Implications for assessment

In the final section of this article, I want to discuss the implications of my proposals for assessment. I want to firstly outline the more general features of English for Academic Purposes, then I will discuss the possible impact of discipline specificity on assessment regimes, and then finally outline the possible effects of LLMs on assessment.

Firstly, I argue that it is important that students are made aware of the importance of using an academic style that is appropriate for the discipline and for the specific context that they are writing for. Secondly, noun phrases and the grammatical structures connected with them seem to be used by all academic disciplines. Thirdly, all academic texts can be defined as being factually source-based texts, and therefore, reading strategies are important to all disciplines. I have suggested that the synthesis grid is particularly useful for essays and literature reviews, but it may well have wider applications. Moreover, in-text citations and the use of reporting verbs and nouns are also important features of academic texts. For novice writers finding the balance between presenting the postulates and data of others and showing their own authorial voice is likely to be problematic for students of all disciplines. These areas can either be assessed as discrete items, or as an integrated assessment. The advantage of the former is that attention is paid to the specific item you are assessing, while the disadvantage of this is that you have more tests to give and grade. The problem with larger integrated tests is that more proficient student can disregard your focus on academic skills, knowing that their general competency will be enough to get a pass.

In terms of discipline specificity, the work of Nesi and Garder (2012) has demonstrated that students are required to write a wide variety of texts, and Martin (2011) has shown that knowledge building is significantly different between academic disciplines. These works have clear implication for the genres and lexical and grammatical features that students are expected to master. While there are hurdles to achieving these goals, I suggest that the benefits of this approach are that students can clearly see the relevancy of their English language tuition, and it is not seen as some kind of remedial exercise.

So how can a degree of discipline specificity be achieved? Firstly, examine the course syllabi, then reach out to the Faculty staff and explain what you are trying to achieve, some will be receptive. For example, I recently started teaching the Academic Writing course element of a Data Science degree course. I took the above steps, and the result was my students wrote an essay comparing and contrasting R vs. Python. For the next iteration, I plan to include an element that focuses on English for Statistics.

I do not have the space to discuss all the implications that LLMs have for the assessment of academic writing, The opportunities and challenges are immense and require a well thought out policy at the institutional level. For example, the Russell group, an organisation that represents 24 of the leading universities in the UK, recently published these guidelines: <rg_ai_principles-final.pdf> (russellgroup.ac.uk). AI policy should not be left to the individual teacher, but here are some of my suggestions. Do not ignore it. I plan to start my classes in October with an exercise – What are the advantages and disadvantages of getting a friend to take your driving test for you? What’s the point of a qualification if you don’t have the requisite skills? Ensure that you have a copy of the student’s writing that was done in exam conditions to provide a reliable point of comparison. There are question marks over Turnitin’s and other’s ability to detect LLM texts, so assess at the university. Finally, seek to continually demonstrate to your students the relevancy of your course to their needs – the effort is worthwhile.

Concluding thoughts

I first looked at the importance of appropriateness and discipline specificity to academic style. I then emphasized the importance of the noun phrase to the grammar of academic writing, before turning my attention to the use of shell nouns. In the second section I underlined the importance of reading strategies to academic writing and showed how a synthesis grid could be used as a staging post between the source texts for an assignment and its first draft, as it encourages purposeful note taking. I then discussed paraphrasing and the synthesising of sources, in the context of the development of a novice writer’s authorial voice through the use of reporting verbs and nouns. The last section examines how the knowledge building of a particular discipline determines its genres of communication, which in turn determines the lexical and grammatical features it employs. Finally, I have discussed the deep impact that AI is having on teaching and assessment several times in the article, and I have suggested how teachers could employ it to assist their teaching and how the danger it poses could be addressed.

The key point that I would like readers of this article to take away, is that university students’ writing is deeply influenced by the academic discipline that they are studying, and therefore I urge tutors to use the practical tools I have suggested to make their courses as discipline focused as possible. I suggest this may increase student engagement, provide opportunities of professional development and raise a tutor’s profile in their faculty.

References

Biber, D., Johansson, S., Leech, G., Conrad, S., & Finegan, E. (1999), Longman grammar of written and spoken English. Harlow: Pearson Education.

Bourdieu, P., Passeron, J-C. (1994), Introduction: Language and the relationship to language in the teaching situation, [in:] P. Bourdieu, J-C. Passeron, M. de Saint Martin (eds.), Academic Discourse. Cambridge: Polity Press, pp. 1-34.

Martin, J. (2011), Bridging troubled waters: Interdisciplinarity and what makes it stick, [in:] F. Christie, K. Maton (eds.), Disciplinarity Functional linguistic and sociological perspectives. London: Bloomsbury Publishing.

Nesi, H., Gardner, S. (2012), Genres across the disciplines: Student writing in higher education. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Sing, C.S. (2013), Shell noun patterns in student writing in English for specific academic purposes, [in:], S. Granger, G. Gilquin, F. Meunier (eds.), Twenty years of learner corpus research: Looking back, moving ahead. Louvain: Presses Universitaires de Louvain, pp. 411-422.

Artykuł został pozytywnie zaopiniowany przez recenzenta zewnętrznego „JOwS” w procedurze double-blind review.